Charging ahead

The UK’s EV transition is progressing. Charging holds the key to further acceleration.

Momentum is growing behind the UK’s transition to electric cars. New EV registrations have recorded double digit annual growth in each of the last three months. Growth rocketed to almost 25% in the crucial number plate change month of September, with a record 56,000 new EVs sold.

The share of electric vehicles in the new car market for the year thus far has now reached 17.8% and it’s expected to rise to 18.5% by the end of 2024. Although this is below the official Zero Emission Vehicle mandate target of 22%, it’s above the effective market-wide requirement of 18.15% as manufacturers can receive credits for exceeding emissions targets on petrol and diesel cars.

Yet despite EVs’ strong showing, some recent media coverage would have you believe they’re struggling to gain traction with drivers and the transition is stalling. With the Autumn Budget approaching, the automotive industry has called for considerable fiscal support to improve new EVs’ price competitiveness to accelerate adoption.

Their most significant ask is to halve VAT on EVs. This would undoubtedly support the transition, but it would cost the Treasury a staggering £7.7 billion by the end of 2026. And it would provide the biggest benefits to the richest drivers buying the most expensive cars.

Onward’s recent report, Electric Feel, highlighted that the Government needs to do more to drive the expansion of affordable, efficient EVs. But we also argued that if any kind of discount were introduced, it should be specifically targeted at low income households that need to drive to work, and be restricted to cheaper EVs.

Another request relating to EV purchase incentives is much more reasonable. Industry would like the Treasury to maintain attractive Benefit in Kind rates for EVs obtained via company car and salary sacrifice schemes. The rate on EVs is currently just 2% compared to around 30% for a typical petrol car. This means a basic rate taxpayer using these schemes would save more than £2,000 in tax on a £40,000 car by choosing an EV rather than a petrol vehicle.

Ahead of the budget, there have been calls to scrap these schemes, with the removal of salary sacrifice benefits capable of saving the Treasury up to £100 million. But this would be a mistake as the schemes account for the majority of new EV purchases at present. The Benefit in Kind rate on EVs is already scheduled to rise to 5% by 2027/28, so the scale of incentive will fall meaningfully over the coming years. And in Electric Feel, we argued the rate should steadily rise to no more than 7% in 2030/31 and 12% in 2035/36. This would result in the tax incentive gradually falling to a minimal amount compared to an employee taking their salary, at the same time as all new car purchases will have to be EVs.

The motor industry’s other VAT-related request is also on the money: cutting the tax on public charging from 20% to 5%, to align with the rate on home charging. Charging has the potential to make EVs financially attractive compared to petrol cars even if they have a higher sticker price. But gaps in public charging infrastructure and barriers to various types of households installing home chargers mean it can be more of a problem than a solution at present. Three of non-EV drivers’ top five concerns about switching to an EV relate to charging.

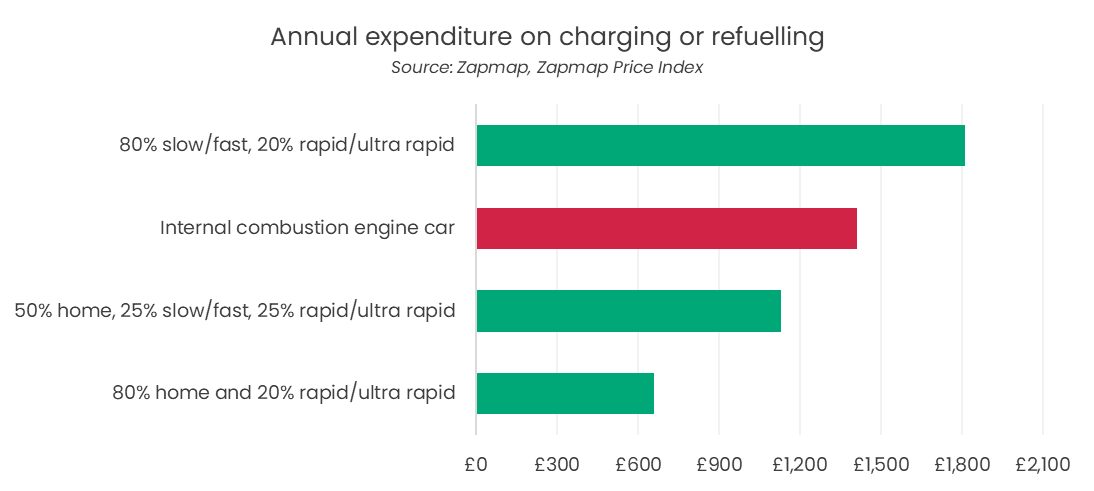

First, when it comes to cost, EVs can provide huge savings on charging compared to refuelling traditional combustion engine cars. Drivers that predominantly charge at home and take advantage of energy retailers’ smart tariffs can save around £750 per year. But those without access to home charging can expect to spend £400 more. Three in ten drivers do not have off-street parking and they face substantial barriers to installing private chargers, as do tenants and leaseholders.

Second, fears over the lack of charging points and difficulty making long journeys both reflect drivers’ awareness of gaps in public charging infrastructure. UK public charge points recently surpassed 70,000 and they are on track to meet the goal of 300,000 by 2030. But their distribution around the country is unequal, with vast disparities at both a regional and local level, and too few chargers where they are needed for long journeys.

London has far more public chargers per car than any other region. But Scotland, Wales and southern regions outside London also have greater provision than many parts of the north and east of England. Many areas don’t have enough chargers in the optimal locations. And most motorway service stations missed the target to install six rapid chargers by the end of 2023.

The disparities are caused by two main problems. First, major funding schemes for public charging installations launched by the previous Government have faced considerable delays. The £950 million Rapid Charging Fund for service stations is still at the pilot stage. The £381 million Local Electric Vehicle Infrastructure fund has progressed further, but the scheme’s short lifespan has made it tricky for local authorities to recruit staff to deliver it.

Plus, local and service station chargers suffer from significant planning delays. Service stations also struggle to obtain sufficient power from the electricity network for large numbers of rapid chargers.

Another challenge with public chargers is cost. There are various reasons why public charging is more expensive than home charging, including higher manufacturing and installation costs. But the 20% VAT rate compared to 5% for private chargers is also a big factor.

There is a strong correlation between the number of public chargers per car and EVs as a percentage of all cars in local areas. And places with more public chargers see stronger growth in EV adoption. So improving the provision of public charging infrastructure, as well as reducing the cost, is key to increasing EV uptake.

Electric Feel highlighted three vital steps to shift charging from being a potential burden for drivers to a cost effective and convenient solution.

First, cheaper, flexible home charging needs to be made available to more households. This entails helping those without driveways, as well as leaseholders and tenants, to access private charging through loan schemes, a ‘right to charge’, and permitted development rights. It also involves expanding smart charging availability by completing the smart meter rollout.

Second, the availability of local charging must be increased and the cost reduced. This can be achieved by optimising funding streams, removing planning barriers to charger installation, and reducing VAT on non-rapid public charging to 5% to align with home charging. The VAT change would cost a comparatively miniscule £35 million in 2025 and rise to just £160 million by 2030, still far below the billions required to halve VAT on EV purchases.

Third, the installation of rapid chargers at service stations and the development of rapid charging hubs needs to accelerate. Rapid Charging Fund money must swiftly begin to be released. And planning barriers that halt the reinforcement of distribution networks for service station grid connections need to be reduced.

Expanding public charging infrastructure and reducing their costs should be a major element of the strategy to achieve mass EV adoption. The upcoming Budget is an ideal opportunity to make some tactical yet significant tweaks that can ensure the UK’s EV transition heads to its intended destination on time.